It was the Air Operations Planner that finally did me in. If the phone wouldn’t ring for that job, it wasn’t going to ring at all.

But let me back up a bit, to 2014 when I retired after 25 years of Air Force (AF) service. I served in a variety of operational, support, and training positions, mostly flying F-16s and other related duties. Along the way, I managed to earn three masters degrees, one from the US Army War College.

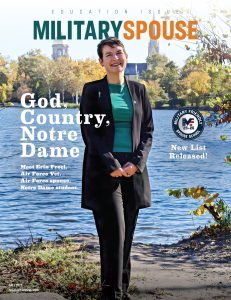

Despite this short biography, this story is not about me—it’s about us, the proud spouses of US military service members. We love our families and our country and we are honored to serve both.

Recently, the president signed an executive order concerning spouse employment, to the cheers of military spouses all around the world. This order acknowledges there is a significant gulf between the good intentions of our national and military leaders and the realities of spouses trying to find a job. Military spouses who’d like to work for the US government only ask for one thing, a level playing field when it comes to competing for jobs at our skill level.

You see, I’m not only a retired Airman, but I’m also a proud military spouse.

Since I retired, we’ve moved on orders three times. Where I live and support my spouse and our family, constraints where I can work. It defines my personal “operational space,” and limits my service possibilities. Unlike many civilian spouses, it’s set by good old Uncle Sam, not me or even us. The realities of military service mean my wife gets a small vote in where she goes, but the family is along for the ride.

And I love that ride, don’t get me wrong. But still, there is within me, within many of us, a remaining desire to serve and contribute outside the home. For spouses interested in government service, our first stop is USAJOBs. Since I retired, I’ve applied for over 70 positions via USAJOBs, approximately 50 of those here in Germany. Of those 70, I’ve been referred four times and interviewed only once. That silent phone on the Air Operations Planner position finally convinced me it was time to take a break from job applications and focus my energies on things where I can contribute to the mission, like this editorial.

How does this editorial contribute? I think the DoD will take the president’s directive seriously. I believe, for the most part, the commanders have the good of their missions and their people as their top priorities. The problem is they have to rely on a bureaucratic process that is failing both the mission and their people. The good news is it can be improved with a few easy tweaks.

Spouses of today are very diverse, have varied educational and aspirational backgrounds. Despite that universally acknowledged reality, family diversity is recognized in theory, but not always in practicality.

Qualified spouses, especially those assigned overseas, are not getting to the “dance floor” for an opportunity to join the employment waltz. This problem is not the fault of military commanders, I was one, and I know a lot of them. Commanders are sometimes frustrated because of the difficulty of finding and hiring skilled civilian employees.

However, at the same time, there may be qualified and motivated spouses, often in the local community. So, where is this disconnect? In some instances, the difficulty lies in the dynamics of hiring Government Service (GS) or Non-appropriated Fund (NAF) positions. It seems the bureaucratic, archaic, service-specific, hiring procedures codified in hiring guidance are failing both commanders and spouses. The reasons for this disconnect are many, but there is no need for a full discussion because there is a better way to do it.

In some cases, the system is working better than in others. Most installations have programs to onboard spouses who want to work. These jobs often focus on support of local installation service programs like the youth center and child care. But for military spouses who want to compete for higher-grade positions, things are much more difficult, especially when assigned overseas.

GS-12 or NAF-4 and above positions are filled before they are even advertised, or only advertised because the hiring authority wants to extend the incumbent in the position and must advertise to do so. Spousal preference, at least in my experience, has been a smokescreen.

To discover the extent of this issue, the DoD could survey its civilian hires of all pay grades and find out what percentage were hired “off the streets,” at the place of current assignment, based on military spouse priority. My guess would be very low numbers, especially for higher-grade positions.

Even spouses who are sometimes able to navigate the system successfully find it can take so long it’s not worth the effort with the time left on assignment, especially overseas. The good news is President Trump’s Executive Order now requires an annual report on the status of spouse hiring, this could force future improvements.

The Pentagon could find one improvement at Foggy Bottom. The Department of State (DoS) Expanded Professionals Associates Program (EPEP) is one of several DoS programs which view inbound families as a team and acknowledge the value of family members who might want a job. DoS sponsors reach out to an incoming family before arrival on station, actively aiding the inbound spouse if they have a desire to work.

The military does none of this but instead requires military spouses to navigate the uncertainty and confusion of the USAJOBs labyrinth. Military spouses are on their own to figure out a complicated and service-specific hiring system. Sure, there are some programs in the family support centers to aid with resumes, interview skills, etc., but there is often little in the way of direct aid or coordination by the Human Resource Office (HROs).

Instead of expecting a military spouse, already burdened by a PCS move, to figure out how to “network” at their new installation and outguess the unclear wording of various job positions, they should be able to submit a generic resume to the local HRO office. They could do this even before they arrive on station. HRO could maintain a bank of available talent, and local hiring authorities would be able to consider local spouses for any job in which they are interested and qualified.

This approach would be a proactive rather than a reactive process and benefit both the spouse and commander having trouble finding qualified candidates. Although to some degree this special hiring authority already exists, it’s not working very well. For example, the Military Spouse Preference Program (Program S) does not apply to overseas spouses, NAF, and excepted service positions. Why should a spouse assigned to an overseas area with their military member be penalized for being overseas? In fact, vague DoD guidance already encourages unique accommodation because of this issue, but Program S should extend to all available and qualified spouses.

To be clear, I’m not arguing unqualified spouses should be hired into any job. For all positions related to national defense, there must be but one criterion; best qualified. But it is no secret that higher-level positions require higher-level qualifications and are often more competitive.

These jobs typically require personal contact and the “inside line.” In my pre-retirement Transition Assistance Program (TAP) training, the instructor mentioned less than 10% of hires come from “blind” resume submission. She stressed the importance of networking to get hired. But how, exactly, does a spouse network when they move every two or three years? Should they hope to meet the hiring authority in the commissary aisles?

The military spouse has no connections, is not a known entity, and cannot even get to that “dance floor” for consideration. The ability for the spouse to network, if any, is likely tied to their active-duty spouse or if they can procure on-post housing. That seems hardly a fair solution for the spouse often left with many of the logistical details at home during family PCS or sponsor deployment, or the spouse who lives off post.

To be sure, there are significant challenges with a preemptive, rather than a reactive hiring approach for military spouses. Security clearances are a significant issue; they are hard enough to complete with employees already in the system.

Hiring a spouse carries the risk of lost developmental effort when that new employee comes to the end of the military member’s assignment. But these challenges are not insurmountable and in the long run could symbiotically benefit commanders and spouses alike. It could be worth the effort to invest developmentally in the entire family rather than focusing solely on the military member, leaving the spouses mostly to fend for themselves.

This effort also has the potential to relieve a significant stressor as 43% of service members consider spousal career opportunities a substantial factor in their decision to remain on active duty. That’s just a bit lower than the 45% of service members who rank patriotism and desire to serve as an important retention factor. And guess what? The military member is probably not the only patriotic member of the household!