Mike Stevens’ career in the U.S. Navy lasted more than three decades and was capped by him being named to the post of most senior enlisted person in that branch of the military.

Now he’s holding his first-ever job in the private sector as chief operating officer of Victory Media, a Moon company that publishes several magazines and reports to help veterans in their search for civilian jobs and post-military educational opportunities.

Among the toughest things Mr. Stevens has had to adapt to since starting at Victory in October are wearing a suit and tie instead of a uniform, and hearing colleagues call him by his first name instead of “MCPON” — the short version of his former title: Navy master chief petty officer.

At Victory, Mr. Stevens, 52, reports to company founder Chris Hale, a retired Navy lieutenant commander, and works alongside other executives who are also veterans. So it’s second nature for them to help him translate corporate lingo and offer tips on how he and his wife can acclimate to a non-military town like Pittsburgh.

For many veterans, though, the jump to business or higher education after service can be difficult, Mr. Stevens said. “The whole disconnect from the military family can take some adjustment,” he said.

According to a 2015 report by the University of Southern California and the Volunteers of America, a nonprofit social services agency based in Alexandria, Va., some of the biggest challenges include undiagnosed or untreated mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Some who have served as commanders in the military expect to be hired in supervisory positions but don’t have the specific skills required for those jobs and don’t want to accept lower positions, the report said.

Another issue is that civilian work cultures are less rigid and more creative, sometimes leaving veterans unsure how to respond to managers and colleagues.

The unemployment rate among all veterans in 2015 was 4.6 percent. For veterans who served in active duty since September 2001 — the group known as Gulf War Era II veterans — the rate was 5.8 percent, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Victory estimates 400,000 active and reserve military personnel leave the service each year and are in the market for jobs or education.

Helping with the transition

For organizations that want to recruit veterans, Mr. Stevens advises establishing a mentorship program.

“What may typically seem a small thing to a new employee can seem overwhelming for a veteran,” he said. “A lot of veterans go to organizations and leave within 12 months because it’s easier to get away from the struggles than to stay.”

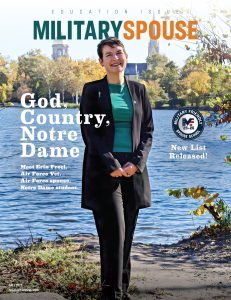

Victory publishes an annual Military Friendly guide that benchmarks companies and schools according to the initiatives and opportunities they provide for former military personnel.

Earning top marks in the 2017 report scheduled for release today are, in the employer category, Marsh & McLennan, a global insurance, financial services and consulting firm; and in the schools category, City College of New York.

Among businesses and schools in the Pittsburgh region that received high marks in various categories were Calgon Carbon Corp., UPMC, West Virginia University, University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, Rosedale Technical College, and Carnegie Mellon University.

Victory has published its list of military-friendly employers since 2003. In 2009, it added a list of schools with the rankings based primarily on surveys completed by the organizations.

This year, the data was broadened to include more feedback from employees and students on how their organizations support veterans; and more benchmarks such as the hiring and promotion rates of veterans among employers. For schools, that includes retention, graduation and job placement rates for veteran students.

A ‘Military friendly’ message

Victory Media was launched in 2001 by three Navy veterans: Mr. Hale; Rich McCormack, company president; and Scotty Shaw, vice president of business development.

Starting with their first print and digital magazine, G.I. Jobs — which was produced in Mr. Hale’s basement — the company has expanded to three more publications; the military-friendly surveys and reports; surveys that rank businesses and schools by availability of STEM programs; and training for organizations that want to recruit and keep veterans.

The privately-held firm declined to disclose revenues. It employs about 50.

In his new job overseeing sales, marketing, technology and human resources, Mr. Stevens sees an opportunity to grow the company by capitalizing on its “military friendly” trademark, which he calls “our most powerful brand.”

Raised in the western Montana town of Arlee on the Flathead Indian Reservation, Mr. Stevens signed up for the Navy as a junior in high school. Two days after his high school graduation, he reported for duty in San Diego.

After completing training to become an aircraft mechanic, he was assigned to his first tour of duty in Rota, Spain, in 1984 and from there was stationed in Norfolk, Va.; Pensacola, Fla.; San Diego; and Puerto Rico.

For six months in 1990-91, he was deployed for combat duty in the first Gulf War.

He flew missions as an air crewman on the USS Tripoli, which was struck and damaged by an Iraqi mine.

Near the end of his final tour in Norfolk in 2012, Mr. Stevens figured it was time to retire. He and his wife, Theresa, sold their house, bought an RV and planned to travel and look for a spot to settle.

Then he was tapped for the prestigious post of master chief petty officer, which required relocating to Washington, D.C., and an office at the Pentagon.

“We sold the RV and my truck, moved into an empty house and started reconstituting stuff,” he said.

During the four years he was master chief petty officer, Mr. Stevens consulted with top Navy officers, worked on leadership initiatives, traveled the world to visit U.S. naval personnel and foreign leaders, visited soldiers in hospitals, and was on hand at Dover Air Force Base each time a fallen sailor’s remains arrived.

Even though the job kept him away from home for days at a time, “It was the honor of my lifetime,” he said.

Now that he and his wife have found a home in Canonsburg, Washington County, and were able to spend their first Thanksgiving together in seven years, Mr. Stevens hopes to become immersed in the Pittsburgh area.

His new mission is to promote veterans to companies and schools.

“Vets are not looking for a handout; they’re looking for a hand up and an opportunity.”