Article originally published at buzzfeed.com

In 2006, as war mounted in Afghanistan and Iraq, the U.S. military began to see the human costs of climate extremes.

As drought hit Afghanistan, one soldier was killed for every 24 convoys to resupply fuel or water. In Iraq, insurgents planted explosives in dams on the Euphrates and Tigris rivers while troops baked in 115-degree summer temperatures.

Elsewhere, drought tied to global warming had sparked war in Darfur. Alternating floods and droughts in Somalia had triggered migration and the rise of warlords. Water scarcity was projected to strike 40% of the world’s nations in coming decades, sparking more wars.

And yet, at that time, the national conversation on global warming revolved around polar bears and Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth. It wasn’t something the Pentagon talked about — until Sherri Goodman stepped in.

Under the auspices of her employer, the CNA Corp., a nonprofit that consults on U.S. military operations, Goodman assembled a new Military Advisory Board. It was about a dozen men — decorated generals and admirals she had known from her own days working at the Pentagon — charged with figuring out what global warming would mean to the military in the 21st century.

Over the course of a year, the new board held dozens of meetings with scientists and soldiers, spies and skeptics. At first, Goodman told BuzzFeed News, there was a lot of doubt among the board members. Most had never thought much about climate change, and some were dubious that human industrial activity was driving up global temperatures.

But instead of arguing over who was to blame, these military leaders thought about climate change as if it were a nuclear weapon, or a political crisis, or any other national security risk. So when putting together their first big report for Congress, they focused on this idea of national defense. And that’s how Goodman coined a wonky, military-sounding term that would turn out to play a pivotal role in reshaping the national debate on climate change.

Climate change, she said, whether rising seas inundating deltas in Bangladesh or stronger hurricanes damaging ships at sea, was a “threat multiplier” — something that makes the powder keg bigger when conflict sparks.

“I just put out there one day, ‘How about we talk about it this way,’ and it stuck,” Goodman told BuzzFeed News from her office in Washington, D.C.

The phrase had a familiar appeal to military men, playing off the Pentagon’s favorite “force multiplier” cliché from the 1990s, which was applied to everything from laser-guided bombs to global positioning satellites. “Threat multiplier” made it into the board’s first report to Congress, released in 2007, along with a sharp and striking message: “Global climate change is and will be a significant threat to our national security.”

Today, Goodman’s term is as popular as ever, thrown around frequently by President Barack Obama, the CIA, the Department of Defense, the State Department, and international organizations such as the G7. Just last month, Vice President Joe Biden used it to explain why the U.S. needs to take a leading role in climate negotiations that start Monday in Paris. Last year, Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel called climate change a threat multiplier for terrorism — exacerbating poverty, disease, migration, and conflict — leading to the Pentagon adding extreme weather to its war games from now on.

“There’s nothing wrong with hugging trees, but climate is still political in this town,” Goodman said. “Reframing the debate made a much broader swath of America comfortable with looking for solutions to climate change.”

It’s not like it worked magic, of course. U.S. climate politics have become intensely partisan in the last decade, so much so that chances of a carbon emissions compromise between Republicans and Democrats have evaporated.

Still, this national security angle is front and center in the Obama administration’s attempts to tackle climate change. In September, Obama highlighted U.S. military interests in a melting Arctic by calling for more Navy icebreakers. Last month, U.S. National Security Adviser Susan Rice said climate change was “at the very center of our national security agenda.” And in the Democratic primary debates, candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders has called climate change the biggest threat to the country.

This profound swing in messaging, insiders say, is largely thanks to Goodman.

“She was the one who brought the generals and admirals around to seeing that environmental security was connected to national security,” political scientist Marc Levy of The Earth Institute at Columbia University told BuzzFeed News. “It took the wind out of the sails of a lot of climate denialists.”

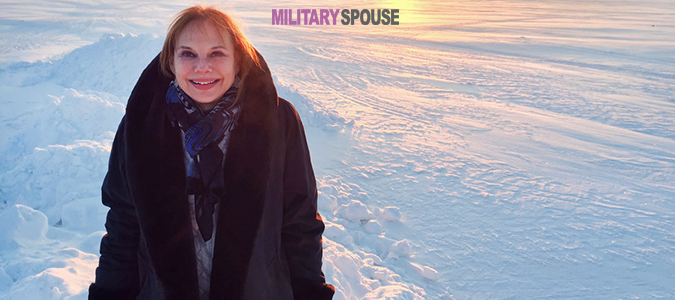

Sitting in her corner office at the Consortium for Ocean Leadership, which she heads, Goodman opens her hands and confesses to some surprise at how her career has progressed. Compact and forthright, the 56-year-old seems like someone at ease giving orders to military officers.

“I had no idea I would spend my career tackling the environment,” she said with a laugh. “My first book was on the neutron bomb,” she added, slapping a leather-bound treatise down on a table. She published the book in 1983, the same year she started Harvard Law School (Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan was her classmate). The book’s political analysis of enhanced radiation nukes was then standard fare for a budding Cold Warrior.

In 1987, when she landed her first job working for Sen. Sam Nunn and the Senate Armed Services Committee, the Cold War “was the world that I expected,” she said.

Scientists were warning about global warming but, as Rice said in a speech last month, the Soviet Union was the “one overarching concern.”

Then the Cold War ended. And suddenly the Department of Energy had to deal with a huge environmental mess left over at dozens of nuclear weapons national labs, a legacy that in 1991 the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment estimated would cost hundreds of billions of dollars to clean up. Those labs were in Goodman’s portfolio as a Senate staffer, where instead of worrying about the costs of nukes, she first moved to worrying about their price to the environment.

The end of the war also meant the U.S. military needed fewer military bases, and about 350 closed in the 1990s. Environmental cleanup of these bases became Goodman’s problem when she moved to the Department of Defense, where she was deputy undersecretary of defense for environmental security from 1993 to 2001. There, she found herself negotiating with towns that didn’t want to pay for cleaning up the environmental damage left behind at firing ranges and ammunition dumps.

A bumpy ride that saw military service chiefs lobbying Congress to hobble environmental reforms, her tenure left the Department of Defense “more accountable, transparent and engaged than ever before” with environmental security, according to American University political scientist Robert Durant.

“At the time people said, ‘The military and the environment, these two things don’t go together,’” Goodman said. Environmental awareness in the U.S. military mostly meant: Don’t dump stuff in the water and don’t pollute the air. Some of the closing bases were EPA Superfund sites, however — certified environmental disasters — and the Defense Department found itself legally obligated to help communities find cleanup solutions. Goodman helped lead these cleanups.

In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol, a United Nations greenhouse gas treaty, put climate change on the Pentagon’s radar for the first time. The Defense Department suddenly had to face the possibility of limits on all the fuels burned by its planes, tanks, and ships. “The U.S. was the only delegation at Kyoto that had two military officers as representatives on its team,” Goodman said.

Kyoto also put climate change on Goodman’s radar — she began to see it as a big environmental risk lurking behind the little ones she faced every day in the base closings. But not much happened after the U.S. Senate refused to sign the treaty toward the end of the 1990s.

The only sign of military interest in climate change after Goodman left the Defense Department came in 2003, when a climate catastrophe scenario was released by a Pentagon think tank and then swiftly downplayed.

Instead, the military’s reconnaissance of climate would come from outside the Pentagon, thanks to Goodman’s new job as general counsel at the nonprofit CNA, and her connections with heavy hitters at the Pentagon.

She assembled the new advisory board with personal pitches to each member. “The generals and admirals on the board were people I knew from my time at the Pentagon and who, yes, I could just pick up the phone and call,” Goodman said. “I just asked, ‘Even if you are skeptical of climate change, could you take a look at this and weigh in?’ And they all said yes.”

Since her days as one of the first woman staffers on the Senate Armed Service Committee, Goodman has never left the male-dominated corridors of military power. It’s never deterred her, she said, because a trail had already been blazed by an earlier generation of women attorneys — notably Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sandra Day O’Connor.

“I think women of my generation knew the whole world was available to them,” Goodman said. “But you were often going to be the first at what you did. So you just did it.”